Unveiling the giants: The Himalayan story

Discover the epic journey of the Himalayas' formation through plate tectonics. Explore how the collision of continents shaped these majestic peaks and continues to impact the region today. Let's dive into the geological wonders!

The birth of a mountain range

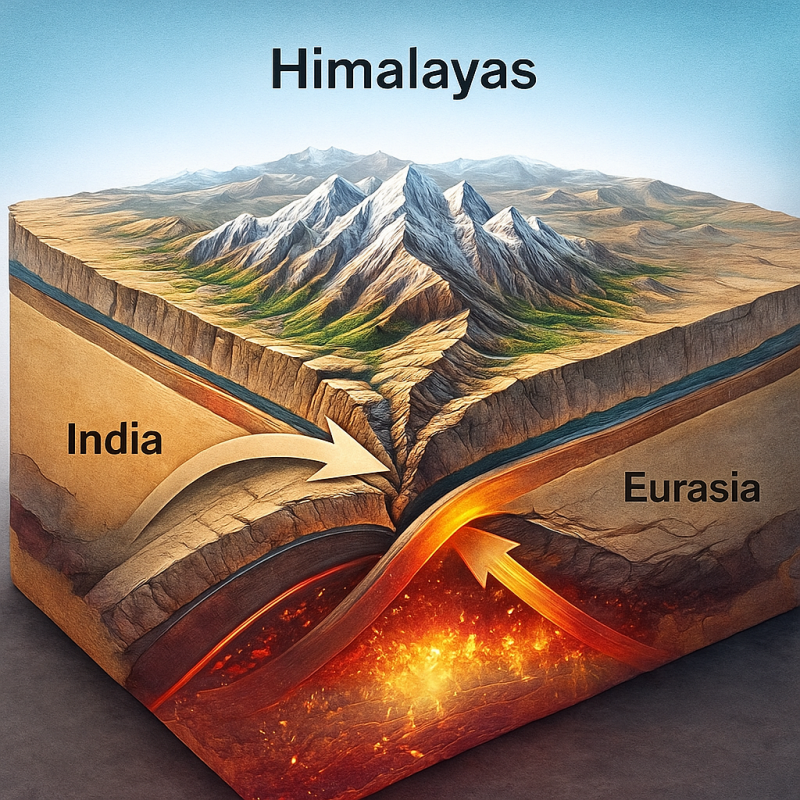

The formation of the Himalayas is explained by plate tectonic theory. This theory states that large rocky plates in the Earth’s rigid outermost layer (lithosphere) converge, diverge or slip past each other over the molten layer of rock in the asthenosphere (National Geographic, n.d.), possibly due to convection currents, ridge push or slab pull (Internet Geography, n.d.).

130 million years ago

tectonic plate motion caused India to drift north, closing the Tethys Ocean (Madden-Nadeau, n.d.).

Between 65 and 45 million years ago

The Himalaya began to form when the Indian tectonic plate collided with and was thrust beneath the Eurasian plate in a process called subduction (Madden-Nadeau, n.d.; The Geological Society, n.d.). The resulting compressional forces squashed and elevated sedimentary deposits and rocks at the margin of the Indian and Eurasian plates creating the massive mountain fold of the Himalayas (Pidwirny & Jones, 2009).

Ongoing uplift

Tectonic plate convergence is ongoing and the Himalayas continue to rise by a few centimetres each year (PBS, 2011).

Seismic activity

As the continents converge, huge stress levels build up within the Earth’s crust which is periodically relieved by earthquakes along landscape faults (USGS,2025).

Rock composition

Distinct geological regions of the Himalaya were formed by faults and thrusts at different times, impacting the rock composition (Government of Nepal, n.d.).

Sedimentary rocks are prevalent in lower elevations and are formed through compression and compaction of accumulated loose sediment (Government of Nepal, n.d.). Higher Himalayan rocks include igneous and metamorphic rocks (Government of Nepal, n.d.) which formed due to the impact of heat and pressure of tectonic collision on buried sedimentary rock (Harris, 2022). Two major rock zones are mainly comprised of igneous plutonic rock which formed from crystallised magma (Harris, 2022).

Evidence of uplift, faulting and erosion

The discovery of ocean bed fossils embedded in sedimentary rock atop Mount Everest provides compelling evidence of geological uplift (Wickrema, 2024). At this remarkable location, you can find an abundance of brachiopods, broken shell fragments, crinoids, and trilobite fossils. Approximately 470 million years ago, the shallow Tethys Ocean was a thriving marine ecosystem. As these hard-shelled organisms perished, their remains gradually settled on the ocean floor. Over time, they were buried by sediment, compacted, and eventually formed limestone. Around 50 million years ago, the Indian subcontinent began its collision with the Eurasian plate. This monumental tectonic event caused the Eurasian plate, along with vast deposits of limestone, to be thrust upward, while the Indian plate subducted beneath it. Over millions of years, the ongoing uplift gave rise to the towering Himalayas. Erosion and faulting eventually stripped away the uppermost layers, revealing these ancient marine fossils in the limestone at Earth's highest summit.